|

|

|

This

melancholy tale of a nurse

and

her experience in the Caribbean is accented by cogent script

writing by Curt Siodmak, Ardel

Wray,

and Val Lewton; moody cinematography

by J. Roy Hunt, and a sensitive

music score by Roy Webb. The Direction

is by Jacques Tourneur, and the

editing by Mark Robson. The melodramatic

title is via RKO Film Executives who were trying to cash in

on the horror film boom that the Universal film studio had brought

about with their various Dracula, Frankenstein and Wolfman movies

in the 1930s-1940s. RKO had set up a special unit under Val

Lewton for the production of these films. This web site discusses

both the film I Walked with A Zombie and its producer,

Val Lewton.

About

the film

"RKO

executives really out-did themselves when they came up with

this title and told Lewton to "make a film to go with

it." But in what was to become standard procedure for

Lewton, he used the title and spooky setting as a cover

to make the story he wanted to, a re-working of Jane Eyre."

From Ken

Yousten's Val Lewton Home Page

Val Lewton was given the title "I Walked

With A Zombie" by the RKO front office, who had drawn it

from an American Weekly article of the same name by writer

Inez Wallace. The result of that

meeting was a depressed state for Lewton. Writer Carl

Siodmak, who had written the screenplays for Frankenstein

Meets The Wolfman, Ghost of Frankenstein, and The Invisable

Woman, the novel Donovan's Brain, among others, worked

with writer Ardel Wray to flesh

out a theme based upon Haitian voodoo. Mark Robson, Zombie's

editor, recalled Lewton being depressed one day, then happily

confidant the next, announcing to his crew that they were going

to make a West Indies version of Charlotte

Bronte's Jane

Eyre. Dedicated to avoiding the formula that pervaded the

Universal horror films, and challenged by the small budgets

given him by RKO, Lewton enlisted the help of his entire crew

in shaping up an artistic film that would go beyond its B-film

origins. Val Lewton was given the title "I Walked

With A Zombie" by the RKO front office, who had drawn it

from an American Weekly article of the same name by writer

Inez Wallace. The result of that

meeting was a depressed state for Lewton. Writer Carl

Siodmak, who had written the screenplays for Frankenstein

Meets The Wolfman, Ghost of Frankenstein, and The Invisable

Woman, the novel Donovan's Brain, among others, worked

with writer Ardel Wray to flesh

out a theme based upon Haitian voodoo. Mark Robson, Zombie's

editor, recalled Lewton being depressed one day, then happily

confidant the next, announcing to his crew that they were going

to make a West Indies version of Charlotte

Bronte's Jane

Eyre. Dedicated to avoiding the formula that pervaded the

Universal horror films, and challenged by the small budgets

given him by RKO, Lewton enlisted the help of his entire crew

in shaping up an artistic film that would go beyond its B-film

origins.

After Siodmak delivered the first version

of the script for Zombie, which, according to later interviews,

was influenced by the paintings of Oscar

Kokoschka, it was then reworked by Wray. She was a young

woman Lewton had hired from out of RKO's Young Writer's Project,

and is the only woman credited to have worked on a Lewton produced

film. The daughter of actress Virginia

Brissac and actor-director John

Griffith Wray, she had started in the RKO reading department.

After Wray, Lewton himself reworked the script a third time,

by which time Siodmak had left the production, and according

to descriptions given by Siodmak much later (he never saw the

actual finished movie) it bears considerable differences from

Siodmak's first draft. After Siodmak delivered the first version

of the script for Zombie, which, according to later interviews,

was influenced by the paintings of Oscar

Kokoschka, it was then reworked by Wray. She was a young

woman Lewton had hired from out of RKO's Young Writer's Project,

and is the only woman credited to have worked on a Lewton produced

film. The daughter of actress Virginia

Brissac and actor-director John

Griffith Wray, she had started in the RKO reading department.

After Wray, Lewton himself reworked the script a third time,

by which time Siodmak had left the production, and according

to descriptions given by Siodmak much later (he never saw the

actual finished movie) it bears considerable differences from

Siodmak's first draft.

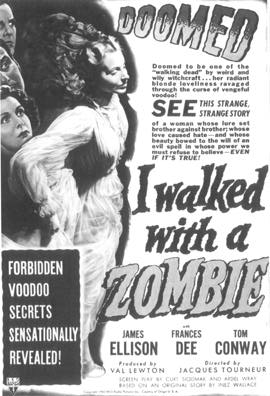

One

of the sensationalistic RKO promo advertisements.

The

Calypso music and Haitian drum rythmns

in Zombie come from a variety of sources. C.

Bakaleinikoff was the musical director, incorporating

in particular the talents of singer/actor Sir

Lancelot, who performs "British Grenadiers"

and "Fort Holland," written in collaboration with

Lewton. According to Jacques Tourneur,

the director, Lancelot functioned as a "...Greek Chorus,

wandering in seven or eight times and explaining the plot."

Roy Webb scored the film, which

includes three Haitian folk "voodoo" songs, and a

unique counterpointing version of Chopin's "E Minor Etude,"

combined with the pulsating drums which dominate much of the

movie soundtrack.

The central recurring image is of the old wooden figurehead

Ti Misery, which is Saint Sebastion, the island's Patron Saint,

a tragic emblem of the pain and suffering for the descendents

of the slaves that live upon the island, a figurehead that came

from Africa on a slave ship. As in Lewton's other films, the

past intrudes upon the present in baleful reminders of former

deeds which mimic present circumstance. (For example, a similar

motif of the repentant Conquistidor parade in Lewton's Leopard Man mimics the state of the film's tragic

peripheral figure, Dr. Galbraith.) In Zombie, those who

came to the island as slaves to European plantation owners are

now servants of a different kind of bondage, a bondage that

then infiltrates and controls the actions of most of the white

masters who control the island. Lewton took pains to bounce

these mirror images back and forth, underlining the sense that

the modern is built upon the foundations of the old. The central recurring image is of the old wooden figurehead

Ti Misery, which is Saint Sebastion, the island's Patron Saint,

a tragic emblem of the pain and suffering for the descendents

of the slaves that live upon the island, a figurehead that came

from Africa on a slave ship. As in Lewton's other films, the

past intrudes upon the present in baleful reminders of former

deeds which mimic present circumstance. (For example, a similar

motif of the repentant Conquistidor parade in Lewton's Leopard Man mimics the state of the film's tragic

peripheral figure, Dr. Galbraith.) In Zombie, those who

came to the island as slaves to European plantation owners are

now servants of a different kind of bondage, a bondage that

then infiltrates and controls the actions of most of the white

masters who control the island. Lewton took pains to bounce

these mirror images back and forth, underlining the sense that

the modern is built upon the foundations of the old.

The

central moment in Zombie is the "night walk"

when the nurse, Betsy, takes the "zombie wife," Jessica,

thru the fields to the Hum Fort. This "night walk"

is a repeated bridge in many of Lewton's films, and characterizes

a literary form reminescent of Joseph Conrad:

(Speaking

of Conrad's Secret Sharer and Heart of Darkness)

"The two novels alike exploit the ancient myth or archetypal

experience of the "night journey," of a provisional

descent into the primitive and unconscious sources of being."

(by Albert Guerard, from the introduction to the Signet Classic

edition.)

Betsy,

and the audience, are plunged into the escalating conflict between

what is real or fancy following this night journey. It should

also be noted that while Zombie is a "flashback"

narrated by Betsy, her last voice-over of narration comes just

before the transition of the story into a heightened dreamlike

state with the "night journey."

The

French film director of Zombie, Jacques Tourneur, later said: "a horrible title

for a very good film - the best film I've ever done in my life."

Film

Notes -

About The Story

- The Cast

Jacques Tourneur

- Val

Lewton - WWW

Links

This Site's Index

- E-Mail

Me

SITE MAP

|

|

Filming

on I Walked With A Zombie began October 26, 1942, and

concluded November 19, 1942.

"One

day at lunch he [Val Lewton] confided he probably would be leaving

the employ of Mr. Selznick before I finished my research job

for him. Half in jest, he insinuated he was being kicked upstairs

for not having sufficiently appreciated either the novel "Gone

With the Wind" or the movie Mr. Selznick made of it. Apparently

Val had tried to persuade Mr. Selznick to forget Margaret Mitchell's

epic novel of the War between the states and film "War

and Peace" or "Vanity Fair," or both, instead.

Val delighted in pointing out similarities in the plots of those

two classics and of Gone With The Wind."

From

DeWitt Bodeen's More from Hollywood, A. S. Barnes and Co., 1977

"He

was given assignments which most contract producers would have

filmed on the back lot and shrugged off as evil necessities,

but he approached each assignment as a challenge. Forced to

submit to exploitation titles, he was determined that the pictures

hiding behind the horror titles should be films of good taste

and high production quality."

From

DeWitt Bodeen's More from Hollywood, A. S. Barnes and Co., 1977

"Given

a sensationalistic title leading viewers to expect little more

than grotesquery and standard chills, Lewton's unit could justifiably

have employed a conventional horror formula, like Universal's,

in Zombie. Simply plunging viewers inti a world threatened

by monsters and eventually releasing them from that dire grip

by vanquishing the threat would have offered audiences a comforting

and not yet trite allegory for the world struggle in which they

were involved [i.e., WW II]. Zombie's narrative mechanism,

however, pointedly works against such a pattern and the dayworld

perspective it implies in favor of a more challenging movement

into the vesperal regions of the psyche."

From

J. P. Telotte's Dreams of Darkness, University of Illinois, 1985

|